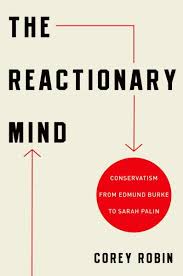

The 2011 edition is available at the New Orleans Public Library.

By Gregory William

Political science professor, Corey Robin, has been hailed as the man who predicted Trump. He does not appear to be a psychic; but in 2011 he did publish a remarkable book (the Reactionary Mind), which traces the historical development of the political right. His analysis shows figures like Sarah Palin and Trump to be very much in keeping with recurrent aspects of this long tradition. They are not the absolute outsiders that they have been described as being (the image of the anti-establishment outsider is something that they themselves have cultivated).

The book traces the long arc of right-wing thought and political movements from the English Civil War of the 1600s, to the French Revolution, to our own time. He finds common features in the thinking of white slave-owners in the American south down to the political machinations of the G.W. Bush administration and its imperialist “war on terror.”

What is right, what is left?

The book is certainly useful for learning about an array of historical episodes, but also because Robin develops a framework for differentiating right from left, based on concrete analysis.

What is right-wing politics, or political reaction (Robin uses the terms interchangeably)? The question is difficult because we see that different figures associated with the right have advocated different things over the course of history. Early conservative figures in France, for example, were pro-monarchy and suspicious of the capitalist market. Today’s U.S. right-wingers, on the other hand, usually say that their commitment to unregulated markets is precisely what makes them conservatives; being pro-market, they say, is the essence of conservativism. Or, they say that the defining feature of conservativism is a commitment to “individual liberty” or “traditional values.”

Making the situation even more confusing, rightists (including neo-fascists) make appeals to the working class, or at least sections thereof (i.e. white workers, or “native” workers against immigrant workers), promising all sorts of things.

Is there a consistent way to distinguish right from left?

Robin argues that, yes, there is. Here is one of his most direct definitions of the right offered up in the book: Conservative thinking comes from “the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back.” He makes a strong case that, in every historical period, conservativism stems from the reaction of the elites (whether monarchs, aristocrats, slave-owners, or present-day capitalists) to progressive movements for liberation and equality. It is a politics of maintaining power, or of restoring power.

The Old South, Guatemala, and the oppressed’s right to speak

One especially interesting aspect of Robin’s analysis is the attention he gives to the politics of the slave-owning class of the old south. He suggests that—in many accounts of the right—too much emphasis is placed on reaction to the French Revolution, whereas, some of the most developed right-wing politics came out of the U.S. south, and that this politics is much more the precedent to the right-wing movements of the 20th and 21st centuries.

For example, he analyzes the statements of John C. Calhoun (1782-1850), the southern politician from South Carolina and seventh vice president of the United States who is often regarded as the chief theorist of the pro-slavery stance. Robin shows how Calhoun was horrified by even the most minimal protests of the oppressed. When the petitions of the enslaved and formerly-enslaved were read in Congress, Calhoun reacted violently. He felt that even allowing the speech of the oppressed in public discourse was tantamount to the beginning of revolution, to the beginning of the end of the “southern way of life,” i.e., the slave system.

One can see parallels in the way that present-day white supremacists have reacted to black athletes kneeling in protest against the widespread murder of black people by police. For these racists, taking a knee is going too far; on the flip side, we can see how these kinds of simple gestures can, in fact, radically shake things up, altering the terrain of struggle in a given period. Unlike Calhoun, we regard that as a good thing.

Similarly, Robin observes how Guatemalan elites (including Catholic clergy) reacted to the 1951-1954 presidency of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. Árbenz, as he is usually known, was the second democratically-elected president of Guatemala. With massive popular support— in a coalition with the Communists and other forces— the Árbenz government enacted a series of progressive policy changes including agrarian reform (breaking up large agricultural estates and giving land to the poor farmers, who were mainly indigenous and who had lacked power since the time of Spanish colonization). Elites were horrified by the mere fact that the poor and oppressed were suddenly entering public life and were allowed to speak. This, in itself, they found intolerable.

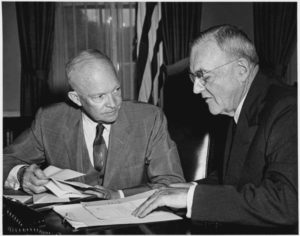

The United Fruit Company, which was active in the country, felt that their profits were being threatened by the Árbenz government, and they called on Washington to overthrow the democratically-elected leader. This was one of the opening salvos of the Cold War. The alliance of the U.S. government, the United Fruit Company, and the old Guatemalan elites imposed a regime of terrible reaction, in the form of military dictatorship, leading to civil war in the following decades. Robin explores all of this in detail.

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, the advocate of the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état that installed the right-wing dictatorship

At any rate, in today’s struggles, we need the kind of sharp lens that Robin affirms. Revolutionaries should be able to see the politics of Trumpism for what it is, but also look at our times more broadly. We have to be able to pose certain questions before the masses. For example, is the Democratic Party a left-wing or a right-wing party? The ultra-reaction of the present-day Republicans should be clear enough.

But if right-wing politics is about preserving existing power arrangements, then the Democratic Party’s consistent militarism, commitment to capitalism, and more, suggests that it is a right-wing party as well. We should not forget the concise statement to this effect from Democratic Party leader, Nancy Pelosi. At a 2017 “town hall meeting” organized by CNN, NYU sophomore, Trevor Hill, suggested to Pelosi that many in the country (especially young people) want the party to move to the left—a claim which he backed up by referencing a Harvard University poll which found that 33% of 18-29 year-olds favor socialism over capitalism. Pelosi responded that, “we’re capitalists, that’s just the way it is.” This is not a party of the working class and oppressed.

We need to have sharp discernment, give that our goal is to strike down the forces of oppression once and for all. We must be able to distinguish friend from foe.