By Isabella Moraga-Ghazi

L’eau Est La Vie camp is being built to protect the water, wetlands and ways of life across the coast of Louisiana from the Bayou Bridge Pipeline (BBP), proposed by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP). On December 14 2017, ETP was granted a permit from the New Orleans District Office of the Army Corps of Engineers giving it the go ahead to lay this pipeline from Nederland, Texas to St. James Parish west of New Orleans.

There has been a long pushback from many different groups, and with the granting of this permit, L’eau Est La Vie is preparing to resist the construction on the front-lines. Cherri Foyltin, one of the many upstanding indigenous women leading the fight against BBP, with blessing from the Atakapa-Ishak Nation, recently bought a large plot of land on the route of the proposed pipeline. The land will be used as a sanctuary for incoming water protectors.

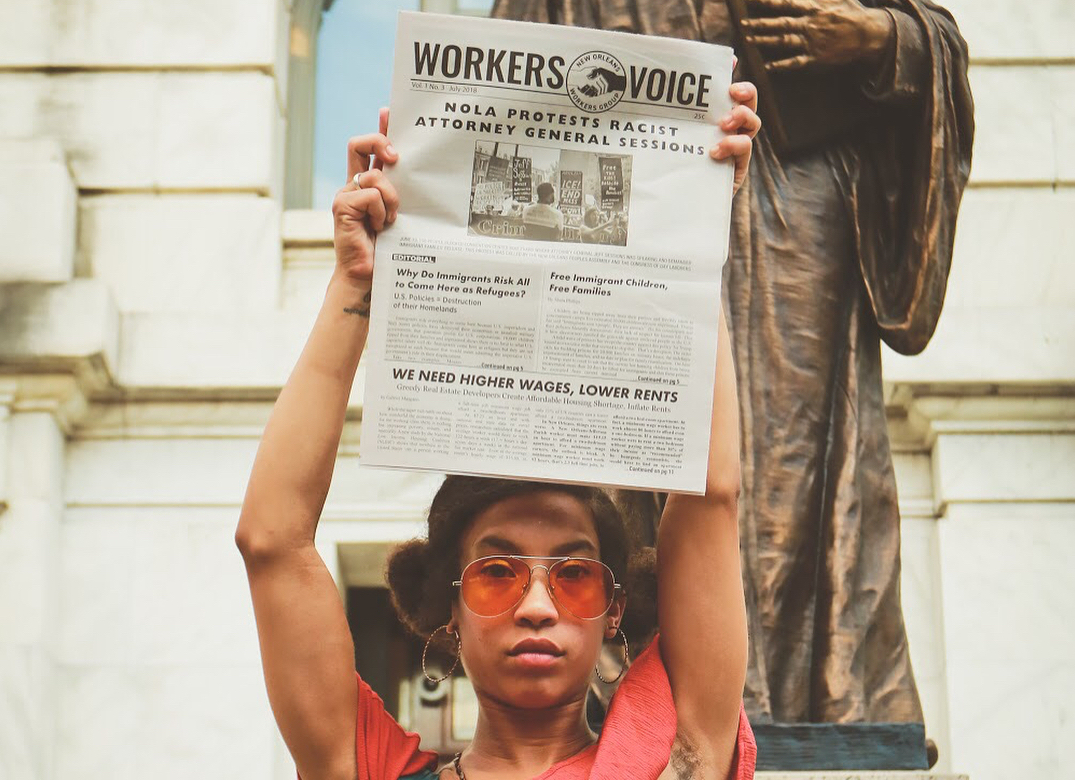

As tension between ETP and local environmental activists rise, this space provides hope that this resistance will not be in vein. Though pipeline construction has not begun yet, it is only a matter of time before water protectors will be standing in protest in front of large metal machines and police barricades. This fight is not futile, as local media would like you to believe, but more people must be willing to speak up.

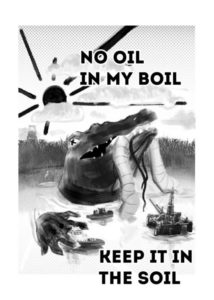

This pipeline affects the livelihood of everyone in southern Louisiana; receding wetlands make hurricanes unstoppable; oil spills make waterways undrinkable and toxic to our seafood; crude chemicals spread cancer and disease to our neighbors, and the list goes on. If you feel for this fight, L’eau La Vie Camp is accepting donations and asking for volunteers. Find out more at nobbp.org.

Stand in solidarity with marginalized communities across southern Louisiana being affected by environmental racism and make our government officials hear us when we say “NO OIL IN MY BOIL! KEEP IT IN THE SOIL!”