Student debt in the US now totals over $1.48 trillion, which is way higher than any other debt in the country. But one person’s debt is another’s asset. Lenders of student debt put together “packages” that tally up all that they’ve lent out to students. Then, they make fast cash selling these packages to big banks with enough money to play around with these investments, like Wells Fargo or Bank of America. These banks then reap all the profits from the interest that former students have to pay—and that’s guaranteed free money for them, since it’s almost impossible to declare bankruptcy on student debt and banks are legally allowed to take from your wages, unemployment benefits, and Social Security checks. The market for this kind of trading is $200 billion, all pocketed by wealthy capitalists who lobby Congress on issues like these regularly.

THE 1907 NEW ORLEANS DOCKWORKERS GENERAL STRIKE

Unionized dockworkers rejected bosses’ white supremacist divide-and-conquer campaign and upheld bi-racial working-class solidarity.

by Malcolm Suber

In the early twentieth century, New Orleans’ unionized dockworkers demonstrated the absolute importance of bi-racial working-class solidarity and rejected the bosses’ use of white supremacy to quash working class aspirations to advance their living conditions. They were following in the footsteps of New Orleans workers who led the general strike of 1892.

A legacy of the 1892 General Strike was the effort to maintain a 50-50, or half-and-half, labor system on the New Orleans docks. Under this arrangement, both Black and white workers insisted that any work crew hired by ship owners be 50% Black and 50% percent white. Workers would labor side by side, performing the same work for the same pay. This was understood by the dockworkers as a tactic to prevent the bosses from lowering all wages by pitting workers against each other by offering more to one group of workers than the other. Both Black and white union leaders recognized that when the owners were allowed to hire without parity between black and white workers, as was the practice before the 1892 General Strike, animosity between black and white workers flared and the working class as a whole suffered a setback.

In October 1901, the separate Black and white unions created the Dock and Cotton Council (DCC) that coordinated the unions of Black and white screwmen, longshoremen, teamsters, loaders and general laborers on the waterfront. An accommodation to the Jim Crow white supremacist system required that the President and financial secretary of the DCC be held by white workers and the vice-presidency and corresponding secretary position be held by black workers. By 1903, the DCC oversaw eight separate unions of Black and white dockworkers with a total of approximately 10,000 members and helped ensure that all unions adhered to the 50-50 rule. In time, the DCC assisted member unions in negotiations with the owners. The DCC was also given the right to call a general port strike.

The New Orleans screwmen were responsible for tightly packing cotton bales in the holds of the ships. This critical task put them atop the labor force on the docks thus providing the screwmen with the highest wages on the docks. However, in contrast to other waterfront laborers, white screwmen in the 1890s refused the 50- 50 arrangements and voted for a quota system limiting the number of black screwmen to a small percentage of the jobs.The black and white locals had separate contracts with different terms and there was no way to support workers in labor disputes. In addition, rumors began to spread that the shipping agents were trying to find ways to remove the 75-bale per day limit instituted by the white screwmen by using black screwmen who would work for lower wages with no limit on bales stowed. These types of racial division led to bloody fights between the screwmen.

By the turn of the twentieth century, all screwmen faced new pressure from the ship owners to increase their output by introducing a new method of loading the cotton bales known as “shoot-the-chute”. This system required crews of 4-5 men to throw down between 400 to 700 bales per day into the holds of ships where other workers waited to pack them. This new system required 4 to 5 times more productivity with no raise in pay. In addition, the work day would no longer be determined by the number of bales but by the whistle of the shipping agent. The screwmen could see that this faster pace would mean less work left for the next day, thus depriving them of pay.

The issue of a fair day’s work and pay became the central issue for the screwmen. In April,1902 the employers’ Steamship Conference declared that only the owners and not any contract had the right to control who worked on the docks and for how long and for what pay.The screwmen fiercely resisted this attack on their living standards. The two screwmen unions agreed to the 50-50 rule; a uniform wage scale limiting the days’ work to 120 bales as opposed the SC demand 400-700. In the fall of 1902, the unions jointly presented their demands to the steamship conference.

The screwmen’s alliance launched a series of strikes from 1902-1903 that forced the Steamship Conference to adopt the production rate and adhere to the 50-50 demands. During these strikes, the screwmen enjoyed the backing of the other waterfront unions and the newly formed DCC.

The bosses tried to break the strike by the usual divide and conquer scheme by spreading a rumor that the black screwmen were violating the agreement and getting more work than white workers. The strike remained united and ended in early December 1902; by December 25 screwmen were packing on average 110 bales per day.

In response to the screwmen’s strike, the bosses instituted two lockouts in 1903. Again, pressing for control of hiring and more production from the screwmen. The screwmen held firm and the bosses were unable to impose new labor standards.

The screwmen were again locked out on October 1, 1903, but they received the support of black and white longshoremen. Shippers led for an injunction and Mayor Paul Capdevielle unsuccessfully tried to mediate. The strikers garnered so much support during the two-week lockout that even scabs refused to cross their lines. Ultimately, the lockout ended when the employers proposed terms that required screwmen to produce 160 bales per day. The unions accepted this proposal and the bosses admitted defeat.

In the fall of 1907, both black and white longshore workers launched an extended general strike against the shipping company bosses. As in 1902-03, screwmen were at the center of the struggle as the bosses resented the contract concessions made in the 1903. When the 1903 contract expired on September 1, 1907, the ship owners sought what they called a ‘parity’ argument, demanding that New Orleans screwmen stow as much cotton as their counterparts in Galveston, TX – a rate of 200 bales per day. On October 4, all of the ship owners locked out the screwmen. In response, the DCC called a general strike. 9000 dockworkers, black and white, struck the New Orleans port in a show of solidarity with the screwmen. Freight handlers from the Southern Paci c line also struck, ending all work on the port.

The bosses responded by bringing in black and white strikebreakers. Some of the strikebreakers quit when they learned they were being used by the bosses and by the extraordinary show of support by entire working class of New Orleans.

During the second week of the strike the owners launched a strong attempt to divide and conquer the unions along racial lines. The owners revived the White League to attempt to intimidate Black strikers. They also appealed to the other dockworkers that this was a fight against the screwmen and they should not lose wages supporting their strike.

On October 11, the screwmen proposed a return to work at the rate of 160 bales per day. The bosses rejected this proposal and demand a rate of 200 bales per day. During the impasse, the bosses worked overtime to divide the workers along racial lines by circulating rumors that the white workers had returned to work, or alternately, that the black workers were returning to work. However, labor solidarity held.

The general strike ended on October 24, 1907 with a compromise plan endorsed and urged by the city’s mayor. Under the compromise, screwmen agreed to return to work at the rate of 180 bales per day. In response to union demands, the agreement included provisions for an investigation into the port’s viability. White supremacy clearly emerged as the screwmen appointed their representatives to the investigative committee along the 50- 50 principle- but white ship owners refused to work with the black representatives. When no resolution could be reached with the racist ship owners, the mayor and state legislature appointed a committee to investigate port conditions. Its focus was cross-racial cooperation among the workers on the New Orleans docks. This cooperation of course violated all norms of Jim Crow segregation. The DCC unions rejected the pressure and held out for working class solidarity to advance working conditions.

WORKER’S LETTER

By Ryan Jones

Three years ago I was a full-time worker at Burger King and like many others, my experience was not good. I was working five days a week, making the federal minimum wage, which is 7.25 an hour. Working full-time i was making $700 a month, which is not a livable wage. Not only was I supporting myself, but also my family. I didn’t receive breaks, and was required to fill multiple positions in the workplace. Like many workplaces, Burger King kept minimum staff on, expecting workers to take on the workloads of multiple people, cutting back on costs at the expense of us workers. The managers would often be aggressive towards workers, yelling at us, snatching our phones away (taking our personal property). They would often yell at us about not “doing our jobs” while we were busting our asses!

They electronically deposited our checks, so we didn’t get our check stubs in person. You could access them online, but without smartphones or computers, it can be very difficult to check and make sure your pay & hours are done right. We in the industry know it’s very common for bosses to shave a couple hours off workers’ checks. They often do this in ways that aren’t noticeable, leaving many workers experiencing wage theft without even realizing it. This is why it’s very important that we have access to our pay stubs.

I feel we should get our pay stubs in person, so we can better hold our bosses accountable. I also feel like everybody should get paid breaks, and a free shift meal. All workers should get a living wage, which at the minimum should be $15 dollars an hour. We all should have a union, so we have the power to demand the dignity and respect we deserve in the workplace. We as workers must make our voices heard, and demand the bosses start listening to what we have to say. We need to get organized as working people. Our bosses aren’t going to give us our rights, we must demand them. We gotta shut shit down.

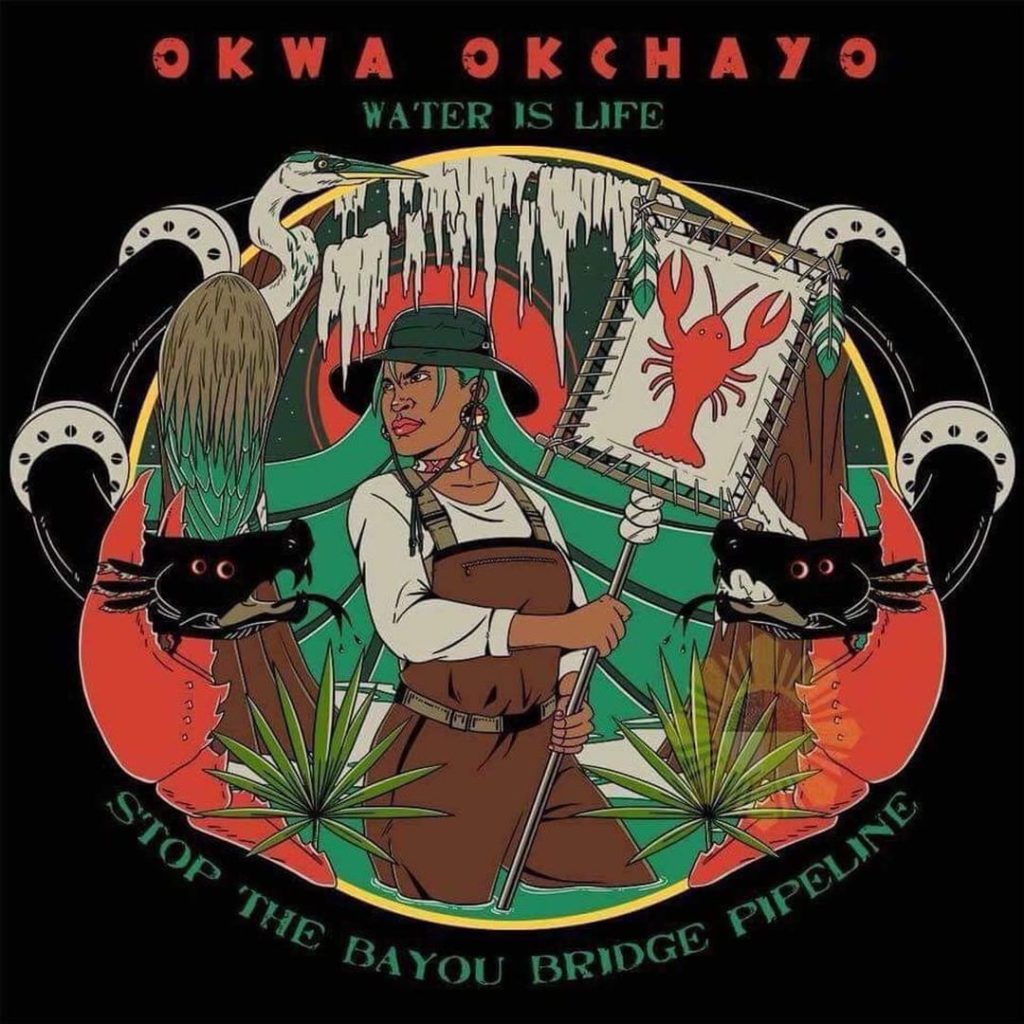

The Bayou Bridge Pipeline Hurts Louisiana

by James York

People everywhere face an uncertain future due to climate change. That is especially true in south Louisiana, where the combination of sea level rise and disappearing coastal wetlands will force many residents to leave within decades. It is undeniable that most of the damage to this area is due to oil and gas exploration and production, and it is undeniable that we are facing a $50 billion budget shortfall just to fund the megaprojects that are supposed to provide some protection against coastal erosion.

In this light, the economic development statistics offered by the proponents of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline are absurd. In exchange for destroying 150 acres of forested wetland and “temporarily impacting” 450 more to build 163 miles of oil pipeline through the Atchafalaya Basin, Our vehemently pro-oil state government has we are being offered only $1.8 million per year in taxes paid to the state and 12 permanent jobs. While the pipeline will continue to make money for its owners and funders year after year, we the people will see nothing for this damage to the wetlands. Pipelines reduce the wetlands’ ability to protect cities and infrastructure from flooding due to hurricanes and irreparably change the hydrology of the affected area, damaging wildlife habitat. We also face the possibility of an oil spill that would threaten the drinking water of some 300,000 people and one of the most productive wetlands in the world, the heart of our $1 billion per year seafood industry. With that in mind, one would expect a reasonable government to say”no” to an obviously bad deal, but in Louisiana we are not so lucky. Our vehemently pro-oil state government has done the opposite (even with a Democratic Party governor).They have given Energy Transfer Partners, the oil corporation behind the hated pipeline, free reign to build despite ongoing legal challenges and violence by local sheriffs that they have hired for off-duty work as private security.

The state government has introduced new legislation in the past three months that pins felony terrorism charges on water protectors who are exercising their first amendment right to peacefully protest. These brave people of the L’eau Est La Vie (Water is Life) camp are living near the pipeline construction and standing up for all of our right to say NO to these projects that could damage our communities forever. Their work can be followed at nobbp.org.

Arrest the Cops Who Murdered Keeven Robinson

The family of Keeven Robinson and the Jefferson Parish NAACP demand cops’ arrest

On May 10, 2018 Keeven Robinson was choked to death by four white cops. The Parish coroner has ruled it a homicide. But the cops are still on desk duty. Taxpayers are still paying their salaries. The police cannot act as judge, jury, and executioner. The murder occurred in the course of arresting Keeven who the cops had been following on nothing more than “suspicion” which smacks of racial profiling.

“I am not comfortable knowing the people who took my brother’s life in cold blood are just walking around like nothing is going on and (are) still getting paid,” Robinson’s younger brother, Randy Martin Jr., told reporters on November 28. “They were getting paid when they took my brother’s life, and they are still getting paid today.”