Instacart is the Uber of grocery shopping. It is a delivery service where customers order through a digital grocery list. Orders are shopped, checked out, and delivered by workers like Vanessa Bain of Palo Alto, California.

Vanessa Bain (VB): I used to work in education and was experiencing burnout. Around four years ago, I decided that I needed to do something different. Things were decent for the first 6-7 months. I was making more money working less hours than I did when I was teaching. I wasn’t coming home totally drained, which was a new feeling for me. I loved it at first.

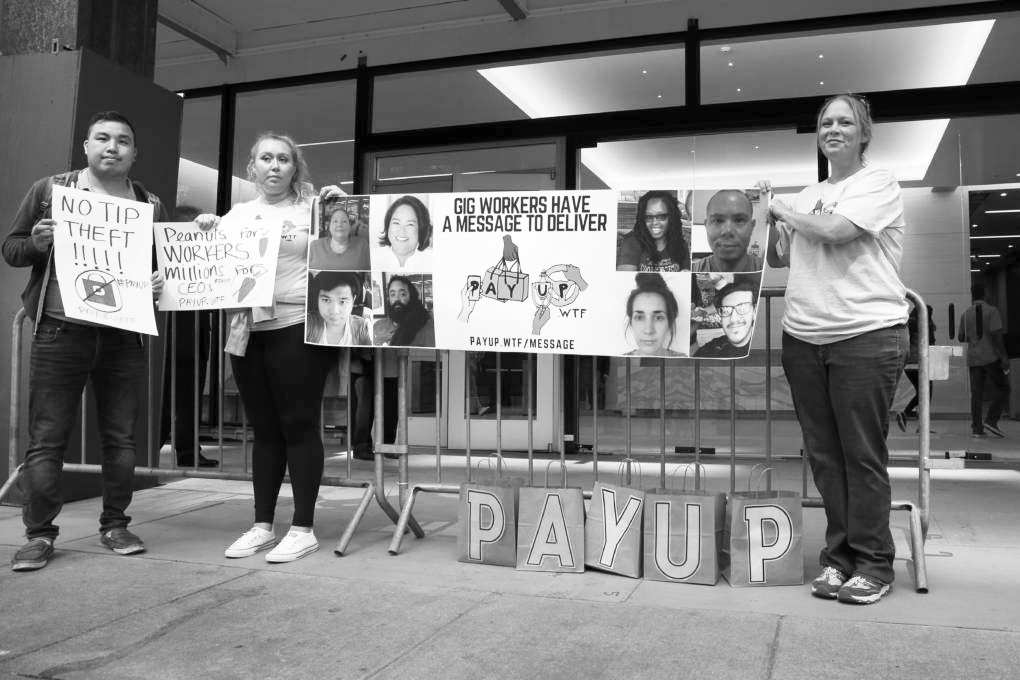

Around September of 2016, they told us they were going to be taking tips out of our apps. Tips accounted for about 50% of my income. I was devastated, and I knew that I couldn’t take this lying down. I typed “#BoycottInstacart” into Instagram and found somebody else who was thinking like me, and we started organizing together. That was my entry into organizing.

Overcoming the obstacles of organizing in the gig economy

VB: There are a lot of obstacles to organizing in the gig economy:

1) We’re misclassified as independent contractors, so we have no protections under the National Labor Relations Act. This also means we’re not entitled to a minimum wage, overtime, rest, and meal breaks. We’re not entitled to draw from programs like workers compensation, unemployment insurance, and disability insurance.

2) The other major hurdle is that we have no centralized workplace. When organizing typically happens, you’re organizing with people in close proximity who you see on a regular basis. Instacart shoppers and Uber drivers are an atomized workforce. There could be a month or two months at a time where you don’t run into someone else who’s doing the same work. The infrastructure that is necessary to organize in a meaningful way is intentionally absent.

The companies want to pit us against each other and call it the hustle and say that we’re our own boss and our own CEO. This is bullshit. They don’t want us to see ourselves as coworkers who could fight back together. Camaraderie breeds collective action, unionizing, and feeling like we’re interconnected. That interconnectivity between folks and the feeling of being accountable to your fellow worker is incredibly important for organizing. The way in which they are implementing this structure is new, but this is centuries’ old bullshit that was regulated away in decades past, but they’re finding ways to bring it back.

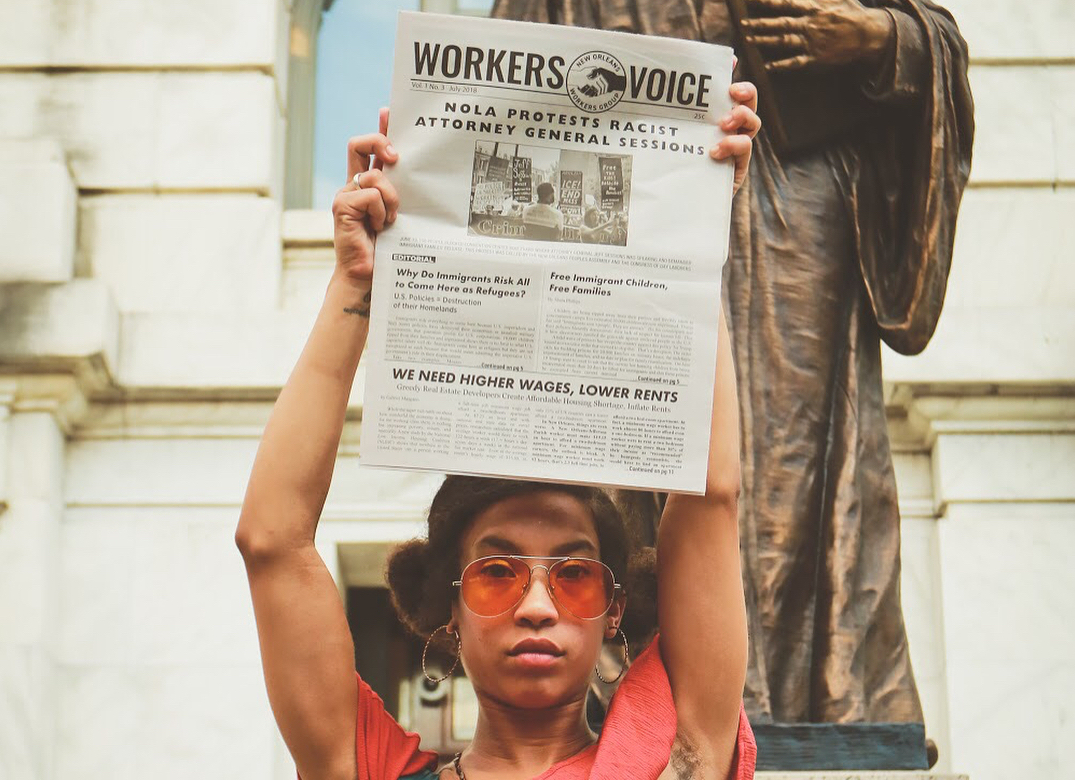

Workers Voice (WV): Capitalists would like to see the whole economy go in this direction. They want to radically increase exploitation, thus increasing their profits. So venture capitalists just threw money at startup companies like Uber and Instacart.

VB: Totally. And none of these are profitable business models. In a nutshell the gig economy is a Ponzi scheme. Not to sound conspiratorial, but that’s really what it is.

Vanessa uses the internet plus face-to-face organizing

WV: How did you face the challenges?

VB: Our organizing is necessarily going to be a hybrid of doing things in person and doing things digitally because we don’t have a centralized workplace. We don’t have a break room, for example. We have to create the equivalent of that online, but not everybody is plugged into social media, so how do you organize? You’re going to have to do it in person. We’re lucky that we do have some sense of shared workspace in grocery stores.

Instacart workers have carried out four walk offs since 2016

VB: Our very first walk off had a couple hundred participants. When we started organizing I don’t think we had the intention of continuing to do this. We did walk outs in 2016 and 2017 and 2019. We did a work slowdown in 2018.

The company has caved to some worker demands, but they are still on the offensive.

VB: Historically, when we do an action, the company gives it about a month and then implements our demands, acting as though it had nothing to do with our action. They don’t want to seem as if they’re responding to worker grievances because workers will see that this works, and we should keep doing it.

The last time they responded by cutting pay. We had a quality bonus, a measly $3 that we were paid for each order when customers rated their experience five stars. It seems like a small sum of money, but a batch can pay as little as $7.00 when you’re shopping and delivering for three customers, so $3 is a big deal. When they cut the quality bonus, it disproportionately hurt people who had done this the longest and were the best at their jobs because it is ostensibly a performance bonus.

Solidarity between shoppers and customers

VB: This outraged a lot of customers. So that was like a secondary boycott. Customers were on Twitter and FB sharing the hashtag “DeleteInstacart.” Instacart’s tactics backfired. Instacart is nothing without shoppers and customers. Pissing off both is really a bad business tactic.

I think that solidarity between customers and shoppers is natural because Instacart is just a software program, but we’re the face of it. Customers have more loyalty to the human being than they do to the company that employs them. And if we’re unhappy, customers know.

Instacart began as a luxury service but it’s becoming more of a service that is oriented toward people who are located in food deserts, no transportation, or people who are disabled and house-bound. We provide a vital lifeline. I saw so many instances of people saying, “I can’t leave my home,” “I can’t go to a grocery store,” “I’m house-bound,” or “I have chronic fatigue and I can’t lift things.” But they are still extending solidarity by boycotting.

2020 should be a lit year for labor

WV: How do you view the strength of the U.S. labor movement right now and in the coming year?

VB: 2019 has been pivotal year for labor. There’s been an explosion of raw energy and cross-sector solidarity. People from all different types of organizing have expressed solidarity. Some are white collar workers who are well compensated, but they are still organizing in their workplaces because they don’t want the technology that they’ve built to be contracted out to the Department of Defense and ICE. They don’t want the technology that they’ve built to be used to oppress people and contribute to climate change.

I’ve been organizing for three and a half years now and I never felt more optimistic than I do now. And I think that we’re gonna see expansion of a lot of the organizing that has sprung up. I think it’s gonna get bigger, and more powerful. Our problems are rooted in capitalism itself.

A lot of current organizing is rooted in the understanding that capitalism is unsustainable. A lot of the problems that we’re struggling with are inherent to capitalism. At some point, capitalism must go. I’m inspired, and I hope that other people can share in that optimism and can feel like when they look at what Instacart workers did in their organizing, they think, “If this person can do it, then I can do it,” and reach out to one another.

The day that we kicked off our walk off, the Google walkout organizers called us and expressed solidarity. They offered an infrastructure that they had available, and we didn’t. They lent their expertise in areas that we didn’t know much about.

I think it’s going to be a lit year for labor! I’m 33. I think that the tides are changing. I think that people are feeling more empowered and emboldened to take bold action.